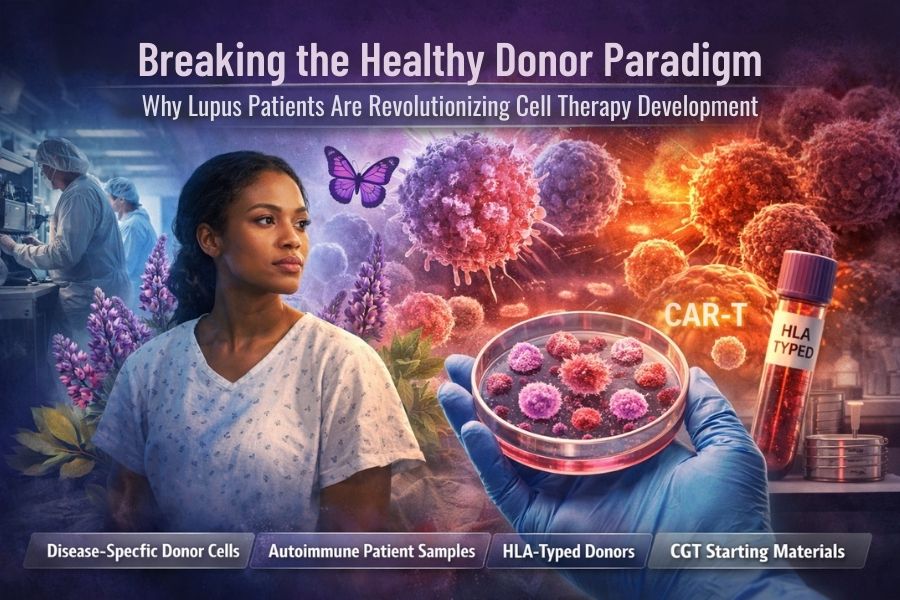

The Uncomfortable Truth About Your “Perfect” Healthy Donors

Here’s a question that should keep every cell therapy developer awake at night: Why are you developing therapies for sick patients using cells exclusively from healthy people?

It sounds almost absurd when stated plainly, yet this has been the gold standard in cell and gene therapy (CGT) development for years. We source pristine leukopaks from healthy donors, develop elegant CAR-T constructs, optimize manufacturing processes, and then act surprised when clinical results don’t match our preclinical promise.

The problem isn’t just about efficacy gaps-it’s about fundamentally misunderstanding the biological terrain where these therapies must operate. That’s why forward-thinking organizations are now expanding access to disease-specific donor cells, including cells from patients with lupus and other autoimmune conditions.

The Immune System Nobody Taught You About

When you work exclusively with healthy donor material, you’re studying an immune system in peacetime. Everything functions as the textbooks describe: T cells respond predictably, cytokine cascades follow known patterns, and cell populations maintain their expected ratios.

But autoimmune disease donors-particularly those with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, or multiple sclerosis-have immune systems perpetually at war with themselves. Their cellular landscapes look nothing like your healthy donor controls.

Consider what’s actually different in lupus donor cells:

Altered T Cell Populations: Lupus patients often show skewed CD4/CD8 T cell ratios, abnormal regulatory T cell function, and T cells with shortened telomeres that behave like aged cells regardless of patient age. Your healthy donor cells won’t replicate this phenotype.

Chronic Inflammatory Priming: Disease-specific donor cells exist in a constant state of low – grade activation. They’ve been swimming in inflammatory cytokines -IL-6, IL-17, IFN-γ-for years. This changes everything from receptor expression to metabolic programming to epigenetic modifications.

Dysfunctional Signaling Cascades: The same pathways you’re trying to manipulate therapeutically may already be broken or rewired in disease states. A CAR-T cell designed using healthy donor material might encounter completely unexpected signaling responses in an autoimmune patient’s body.

Altered Microenvironment Interactions: Patient- derived immune cells have adapted to function (or malfunction) in specific tissue environments. They express different adhesion molecules, respond differently to chemokines, and interact with stromal cells in ways healthy cells simply cannot model.

Why Your Preclinical Data Might Be Lying to You

Let’s talk about the translation gap that haunts cell therapy development.

You run beautiful preclinical studies. Your CAR-T cells eliminate target cells with 95% efficiency in vitro. Your cytokine release profiles look manageable. Your expansion kinetics are textbook perfect. Then you move to clinical trials, and suddenly nothing performs as expected.

What happened?

You tested your therapy using CGT starting materials that don’t represent your patient population. It’s like testing a four-wheel-drive system exclusively on paved roads and then wondering why it underperforms in mud.

The immune dysregulation present in autoimmune disease donors creates conditions that are impossible to simulate with healthy cells:

Pre-existing Autoantibodies: Lupus patients may have antibodies that interfere with cell processing, transduction efficiency, or even therapeutic cell survival. You won’t discover this until you’ve already invested millions in a manufacturing process

Medication Interactions: Many autoimmune patients take immunosuppressants, corticosteroids, or biologics that fundamentally alter how their cells behave. Disease-specific donor cells from patients on various treatment regimens let you understand these interactions during development, not during Phase II failures

Exhaustion and Senescence Markers: Chronic disease drives immune cells toward exhaustion or senescence states. If your therapy relies on robust T cell expansion or persistence, testing with healthy donor material may give you false confidence about what’s achievable in real patients.

The HLA Matching Revolution You’re Missing

Here’s where disease-specific donor cells become even more critical: HLA matching in autoimmune contexts.

Certain HLA alleles are correlated with autoimmune disease risk. HLA-DR2 and HLA -DR3 in lupus. HLA-DR4 in rheumatoid arthritis. HLA-DQ2/DQ8 in celiac disease.

(References: [Source][Source][Source])

When you develop allogeneic cell therapies for autoimmune indications, you need to understand how your therapeutic cells interact with these high-risk HLA types. But most healthy donor databases aren’t enriched for disease-associated HLA alleles-they reflect general population frequencies.

By working with lupus donor cells and other autoimmune disease donors, you gain access to HLA – typed donors carrying the exact alleles your patient population will have. This allows you to:

- Test for alloreactivity against disease-relevant HLA types

- Optimize HLA-matching strategies for your specific indication

- Identify unexpected HLA-restricted responses that could impact safety or efficacy

- Build donor banks with HLA diversity that mirrors your clinical trial population

This isn’t theoretical. Multiple CGT programs have failed or stalled due to unexpected HLA-related issues discovered only in late-stage trials. Disease-specific donor cells let you de-risk these concerns during early development.

The Economic Case for Patient-Derived Starting Materials

Let’s talk money, because ultimately, that’s what keeps programs alive or kills them.

Using only healthy donor material might seem cost-effective initially. Healthy donors are abundant, their cells are robust, and procurement is straightforward. But consider the hidden costs:

Failed Batch Economics: When your manufacturing process is optimized for healthy cells but must work with patient cells, you see higher batch failure rates in clinical manufacturing. Each failed batch costs $50,000-$500,000 depending on your product complexity.

Clinical Trial Redesigns: Discovering that patient cells behave differently than your preclinical healthy donor cells often requires protocol amendments, additional safety monitoring, or dose escalation changes. These delays cost months and millions.

Regulatory Friction: When FDA reviewers see a massive gap between your IND-enabling studies (healthy donors) and your proposed patient population (autoimmune disease), expect questions, additional requests, and slower approval timelines.

Comparability Exercises: If you eventually recognize the need for disease-specific donor cells and want to modify your process, you’ll face expensive comparability studies to demonstrate your new approach still produces the same product.

Now contrast this with developing using disease-specific donor cells from the start:

- Your process is optimized for the cells you’ll actually manufacture with

- Your safety data reflects real-world patient cell behavior

- Your regulatory package tells a coherent story from bench to bedside

- Your manufacturing scale-up is de-risked because you’ve already handled “difficult” cells

The upfront investment in accessing autoimmune disease donors pays for itself many times over in reduced late-stage failure risk.

What “Recallable Disease Donors” Actually Means for Your Program

One of the most underappreciated advantages of working with established disease-specific donor cells programs is recallability.

When you source patient-derived immune cells from HLA-typed donors with documented autoimmune conditions, you’re not just getting cells, but you’re getting access to a longitudinal resource. Need to retest after modifying your construct? Recall the same lupus donor. Want to compare how cells from patients at different disease stages respond? Recall donors with varying disease activity scores.

This is impossible with anonymous, one-off healthy donor procurement. It’s transformative when working with established autoimmune disease donor banks where patients are:

- Fully consented for research studies and recall

- Comprehensively HLA-typed and characterized

- Documented for disease status, medications, and disease duration

- Available for repeat donations under IRB-approved protocols

Recallable disease-specific donor cells eliminate one of the biggest variables in CGT development: donor-to-donor variability. You can iterate on your process using cells from the same donors, creating true longitudinal datasets that reveal whether changes in outcomes are due to your modifications or just different donor biology.

The Practical Path Forward

So how do you actually integrate disease-specific donor cells into your development program?

Start in Discovery: Don’t wait until clinical development to think about patient-relevant cells. Run early proof-of-concept experiments with both healthy and autoimmune disease donors. The differences you discover will inform every downstream decision.

Build Hybrid Strategies: You don’t need to abandon healthy donor material entirely. Use healthy donors for process optimization and manufacturing validation where consistency matters most but use patient-derived immune cells for critical efficacy, safety, and translational studies.

Partner with Specialized Suppliers: Not all cell procurement organizations can provide disease- specific donor cells with the documentation, quality, and recallability you need for regulated development. Work with suppliers who have established relationships with autoimmune patient communities, proper IRB oversight, and GMP-compliant processing.

Document Everything: When you use lupus donor cells or other disease – specific donors in your development program, document the rationale, characterization data, and outcomes meticulously. This documentation becomes part of your regulatory narrative about why your therapy is designed for real-world patients.

Engage Regulators Early: In your pre-IND meetings, discuss your strategy for incorporating disease-specific donor cells. FDA and EMA reviewers increasingly recognize the value of this approach, but they want to see it thought through carefully, not bolted on as an afterthought.

The Future Is Patient-Centric Development

The expansion of CGT starting materials to include lupus patients and other autoimmune disease donors isn’t just about offering more options, it’s about fundamentally rethinking how we develop cell therapies.

For too long, the cell therapy field has operated under the assumption that healthy donor biology is a suitable proxy for patient biology. We’ve treated disease as something that happens to otherwise normal cells, rather than recognizing that chronic disease fundamentally rewires cellular programming.

The developers who recognize this, and who build their programs from the start using disease-specific donor cells that reflect their target patient population, will be the ones with therapies that actually work when they reach patients.

Because here’s the truth nobody wants to say out loud: if your cell therapy only works with healthy donor cells, you don’t have a therapy for sick patients. You have an expensive science experiment that will fail in the clinic.

The biological reality of autoimmune disease donors – the inflammatory priming, the altered signaling, the exhaustion markers, the medication effects – isn’t a bug in your system. It’s the system. And if your therapy can’t handle that reality, no amount of optimization using patient-derived immune cells from healthy people will save it

The question isn’t whether to incorporate disease-specific donor cells into your development program. The question is whether you can afford not to.